January 31, 2021

Introduction to Docker

Brief primer on Docker

What is Docker?

Docker, simply put, is a set of tools for building and running applications inside containers.

The interesting part is the containers themselves; Docker is “just” the tooling that makes them easy to build, run, and share.

So what’s a container?

A container packages up your code and everything it needs to run: libraries, runtimes, config, etc. Containers are lightweight and can run in different environments without you having to tweak much. That’s the real win: I can build and test an app on my Mac, then deploy it to some Linux box on AWS, and it behaves the same. I don’t have to obsess over small differences between my dev and prod environments. With Docker, I can be reasonably confident that what works in development will also work in production.

Containers vs Virtual Machines

Containers are almost like virtual machines.

A virtual machine (VM) emulates an entire computer system. For example, you can run Windows inside a VM on your Mac. To do that, the VM needs a way to translate between the guest OS (Windows in this example) and the actual hardware. That’s where the hypervisor comes in: it provides a layer of virtual hardware so the guest OS thinks it’s talking to real hardware, when in fact it’s talking to the hypervisor.

The tradeoff: VMs are heavy. Each VM needs its own full OS and a bunch of resources (CPU, RAM, disk). They’re powerful, but not exactly lightweight.

Containers take a different approach.

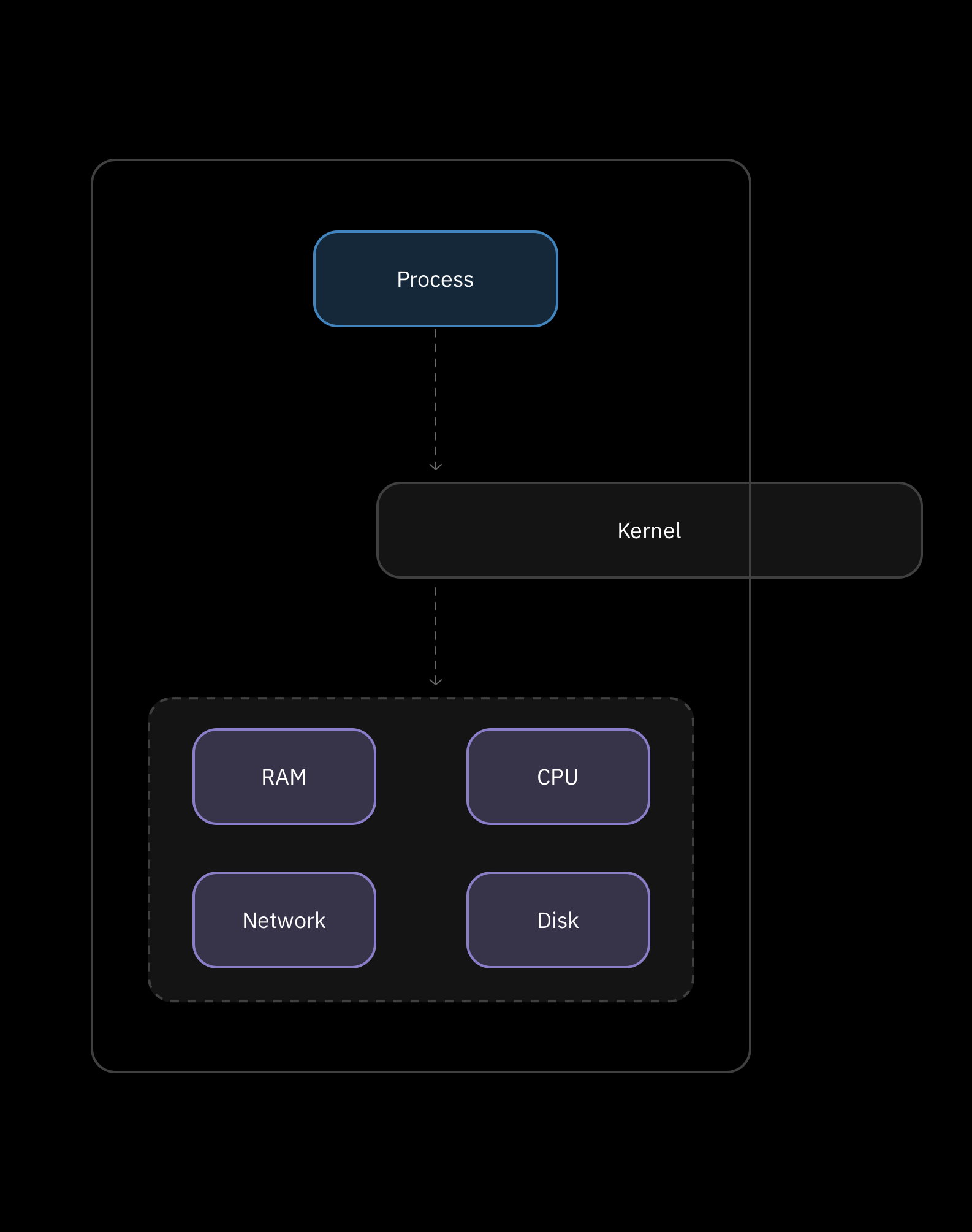

Instead of emulating a full machine, a container uses the host OS kernel (most often Linux) and runs on top of it. Under the hood, containers lean on a couple of key kernel features:

- Kernel: The kernel is the core part of the OS that controls access to hardware resources (CPU, RAM, disk, etc.). Processes make system calls to the kernel when they need those resources.

- Namespaces: Namespaces let the kernel “slice” its resources so different processes see different views of the world. For example, two processes can have their own process trees, network interfaces, or mount points. With namespaces, we can isolate resources per process or group of processes.

- Control groups (cgroups): Cgroups let us limit and account for how many resources a process (or group of processes) can use—CPU, memory, and so on.

Putting that together, we can think of a container as a process (or group of processes) that:

- Shares the host kernel

- Runs in isolated namespaces

- Has its resource usage controlled via cgroups

I made a drawing to visualize this idea:

Docker on macOS

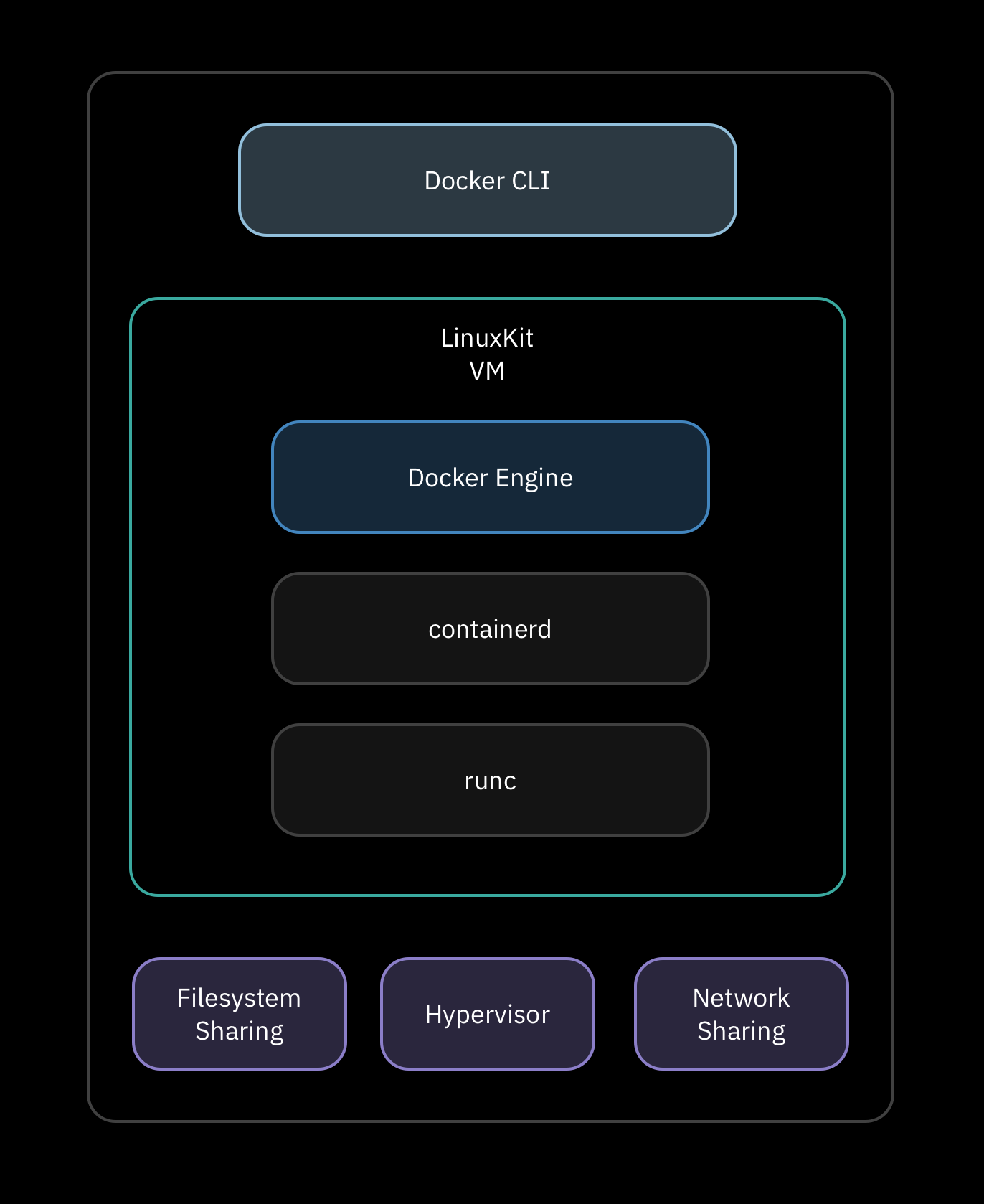

One thing to call out is that if you’re running Docker on macOS, the architecture is slightly different. Docker Desktop doesn’t run containers directly on macOS. Instead, it starts a small LinuxKit VM behind the scenes. Inside that VM you’ll find the Docker Engine, containerd, and the containers themselves, all running on a real Linux kernel. The Docker CLI you run on your Mac talks to the Docker Engine inside that VM over a socket that Docker Desktop exposes for you.

Under the hood, Docker Engine doesn’t directly fiddle with namespaces and cgroups. It delegates that work to containerd, a separate daemon whose whole job is to manage containers.

When you run docker run, the CLI talks to Docker Engine, Docker Engine asks containerd to create a container from an image, and containerd sets up the filesystem, isolation (namespaces/cgroups), and then hands things off to a lower-level runtime called runc. runc is a small tool that actually talks to the Linux kernel to create the container process with the right namespaces and cgroups applied. On macOS all of that happens inside the LinuxKit VM; in production on a Linux host, it happens directly on that machine without the extra VM layer.

Images

If you’ve heard of Docker, you’ve almost certainly heard of images.

An image is:

- A snapshot of a filesystem (all the directories/files your program needs)

- Plus a startup command that should be run when the container starts

You can think of it as a template. A container is a running instance created from that template.

Very roughly, when we turn an image into a running container, the kernel (with help from Docker and containerd) will:

- Set up isolated namespaces and cgroups for the container.

- Mount the filesystem described by the image into that container’s view of the world.

- Run the image’s startup command inside that environment.

That startup command has to exist inside the filesystem snapshot as an executable.

Dockerfiles

So how do we create an image? That’s where Dockerfiles come in.

A Dockerfile is a small config file that describes: • Which base image to start from • What files to copy in • What commands to run while building the image • What command to run when the container starts

At minimum, a Dockerfile looks something like:

FROM some-base-image

# build steps here...

CMD ["./your-program"]We always start with a base image because, by default, an image is empty. The base image gives us an initial set of programs and libraries we can build on top of. You pick a base image that already has the tools you care about.

Building and Running an Image

Once we’ve written a Dockerfile, we can build an image from it by running, in the same directory:

docker build .This will output an image ID for the newly built image.

To run it as a container:

docker run <image-id>And just like that, you’ve got a container running based on your image.

Now that we’ve got the basic terminology out of the way—containers, images, Dockerfiles—we can finally start building something real. In the next post, we'll explore how we can dockerize a real application.